Lempel-Ziv-Storer-Szymanski

Lempel-Ziv-Storer-Szymanski, which we’ll refer to as LZSS, is a simple variation of the common LZ77 algorithm. It uses the same token concept with an offset and length to tell the decoder where to copy the text, except it only places the token when the token is shorter than the text it is replacing.

The idea behind this is that it will never increase the size of a file by adding tokens everywhere for repeated letters. You can imagine that LZ77 would easily increase the file size if it simply encoded every repeated letter “e” or “i” as a token, which may take at least 5 bytes depending on the file and implementation instead of just 1 for LZSS.

Implementing an Encoder

Let’s take a look at some examples, so we can see exactly how it works. The wikipedia article for LZSS has a great example for this, which I’ll use here, and it’s worth a read as an introduction to LZSS.

So let’s encode an excerpt of Dr. Seuss’s Green Eggs and Ham with LZSS (credit to Wikipedia for this example).

I AM SAM. I AM SAM. SAM I AM.

THAT SAM-I-AM! THAT SAM-I-AM! I DO NOT LIKE THAT SAM-I-AM!

DO WOULD YOU LIKE GREEN EGGS AND HAM?

I DO NOT LIKE THEM,SAM-I-AM.

I DO NOT LIKE GREEN EGGS AND HAM.

This text takes up 192 bytes in a typical UTF-8 encoding. Let’s take a look at the LZSS encoded version.

I AM SAM. <10,10>SAM I AM.

THAT SAM-I-AM! T<15,14>I DO NOT LIKE<29,15>

DO WOULD YOU LIKE GREEN EGGS AND HAM?

I<69,15>EM,<113,8>.<29,15>GR<64,16>.

This encoded, or compressed, version only takes 148 bytes to store (without a magic type to describe the file type), which is 77% of the original file size, or a compression ratio of 1.3. Not bad!

Analysis

Now let’s take a second to understand what’s happening before you start trying to conquer the world with LZSS.

As we can see, the “tokens” are reducing the size of the file by referencing pieces of text that are longer than the actual token. Let’s look at the first line:

I AM SAM. <10,10>SAM I AM.

The encoder works character by character. On the first character, ‘I’, it checks it’s search buffer to see if it’s already seen an ‘I’. The search buffer is essentially the encoder’s memory, for every character it encodes, it adds it into the search buffer so it can “remember” it. Because it hasn’t seen an ‘I’ already (the search buffer is empty), it just outputs an ‘I’, adds it to the search buffer, and moves to the next character. The next character is ‘ ‘ (a space). The encoder checks the search buffer to see if it’s seen a space before, and it hasn’t so it outputs the space and moves forward.

Once it gets to the second space (after “I AM”), LZ77 comes into play. It’s already seen a space before because it’s in the search buffer so it’s ready to output a token, but first it tries to maximize how much text the token is referencing. If it didn’t do this you could imagine that for every character it’s already seen it would output something similar to <5,1>, which is 5 times larger than any character. So once it finds a character that it’s already seen, it moves on to the next character and checks if it’s already seen the next character directly after the previous character. Once it finds a sequence of characters that it hasn’t already seen, then it goes back one character to the sequence of characters it’s already seen and prepares the token.

Once the token is ready, the difference between LZ77 and LZSS starts to shine. At this point LZ77 simply outputs the token, adds the characters to the search buffer and continues. LZSS does something a little smarter, it will check to see if the size of the outputted token is larger than the text it’s representing. If so, it will output the text it represents, not the token, add the text to the search buffer, and continue. If not, it will output the token, add the text it represents to the search buffer and continue.

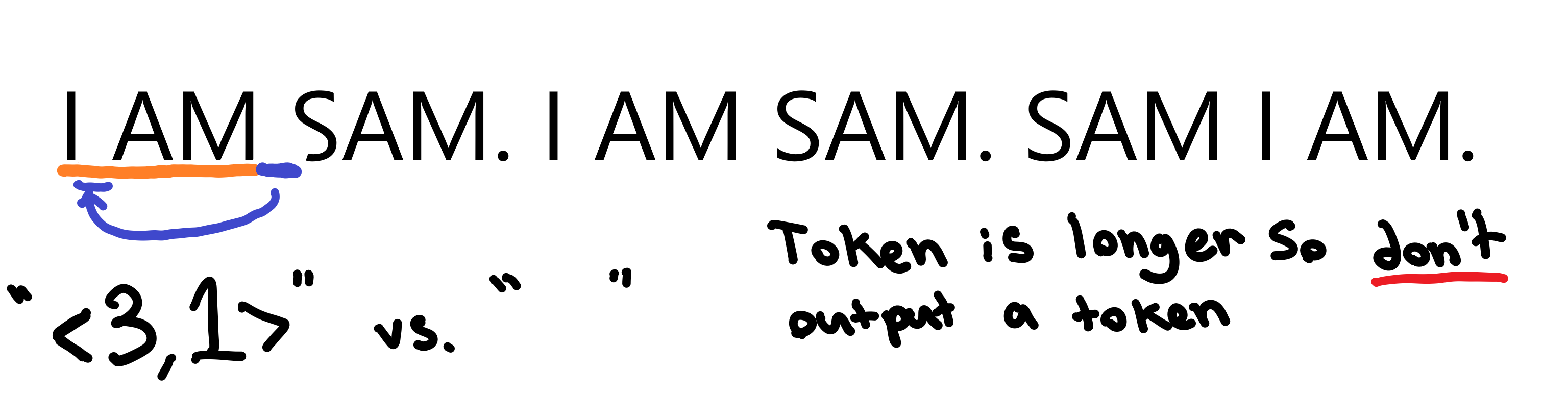

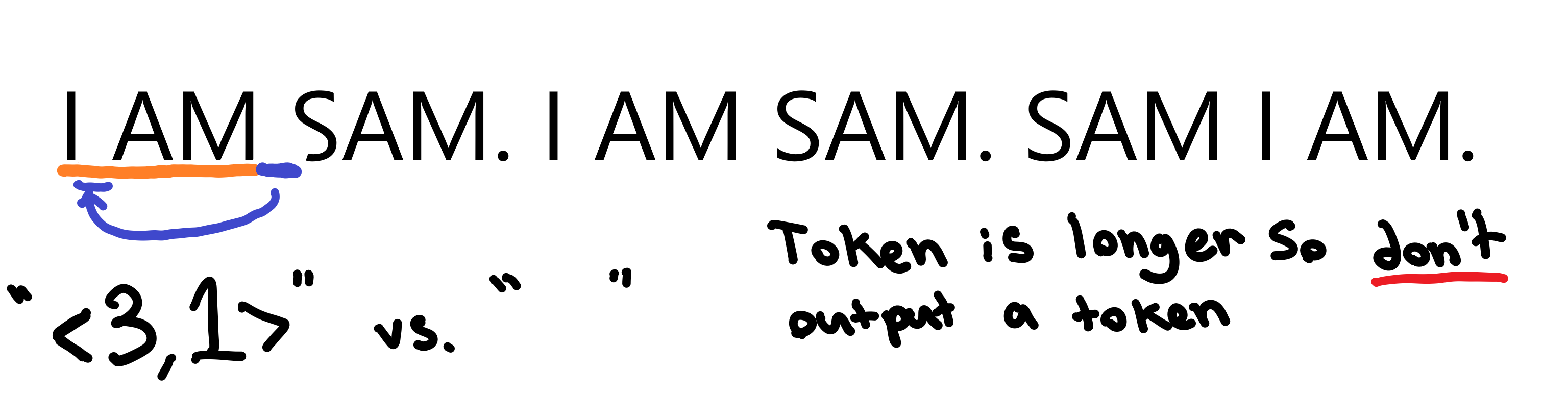

Coming back to our example, the space character has already been seen, but a space followed by an “S” hasn’t been seen yet (“ S”), so we prepare the token representing the space. The token in our case would be “<3,1>”, which means go back three characters and copy 1 character(s). Next we check to see if our token is longer than our text, and “<3,1>” is indeed longer than “ “, so it wouldn’t make sense to output the token, so we output the space, add it to our search buffer, and continue.

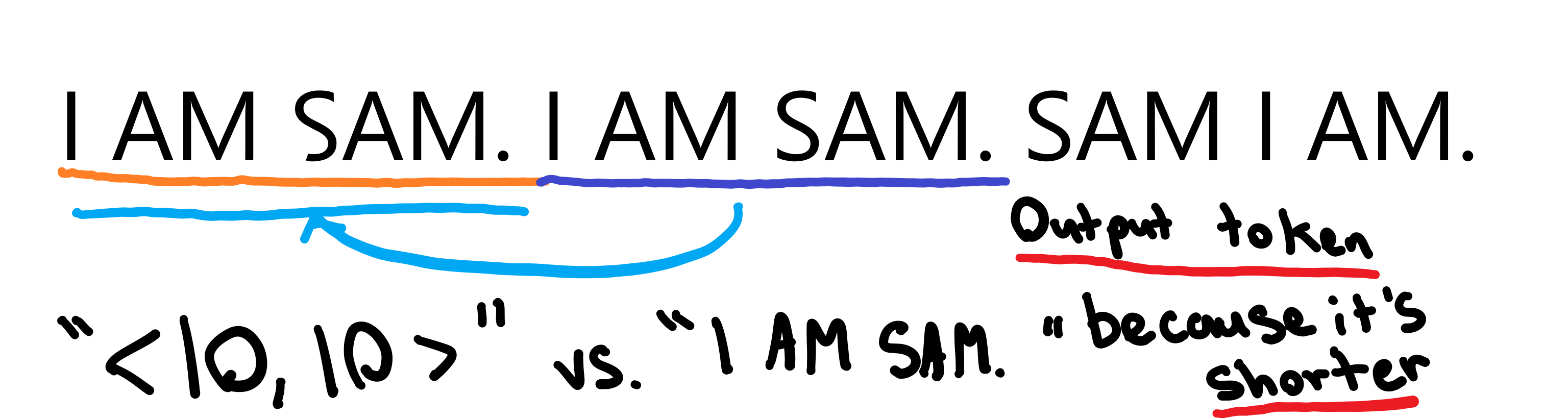

This entire process continues until we get to the “I AM SAM. “. At this point we’ve already seen an “I AM SAM. “ but haven’t seen an “I AM SAM. S” so we know our token will represent “I AM SAM. “. Then we check to see if “I AM SAM. “ is longer than “<10,10>”, which it is, so we output the token, add the text to our search buffer and continue along.

This process continues, encoding tokens and adding text to the search buffer character by character until it’s finished encoding everything.

Takeaways

There’s a lot of information to unpack here, but the algorithm at a high level is quite simple:

- Loop character by character

- Check if it’s seen the character before

- If so, check the next character and prepare a token to be outputted

- If the token is longer than the text it’s representing, don’t output a token

- Add the text to the search buffer and continue

- If not, add the character to the search buffer and continue

- If so, check the next character and prepare a token to be outputted

It’s important to remember that no matter the outcome, token or no token, the text is always appended to the search buffer so it can always “remember” the text it’s already seen.

Implementation

Now let’s take a stab at building our very own version so we can understand it more deeply.

As with most of these algorithms, we have an implementation written in Go in our raisin project. If you’re interested in what a more performant or real-world example of these algorithms looks like, be sure to check it out. However for this guide we’ll use Python to make it more approachable so we can focus on understanding the algorithm and not the nuances of the language.

Character Loop

Let’s get started with a simple loop that goes over each character for encoding. As we can see from our takeaways, the character-by-character loop is what powers LZSS.

text = "HELLO"

encoding = "utf-8"

text_bytes = text.encode(encoding)

for char in text_bytes:

print(bytes([char]).decode(encoding)) # Print the character

Output:

H

E

L

L

O

Although the code is functionally pretty simple, there’s a few important things going on here. You can see that looping character-by-character isn’t as simple as for char in text, first we have to encode it and then loop over the encoding. This is because it converts our string into an array of bytes, represented as a Python object called bytes. When we print the character out, we have to convert it from a byte (represented as a Python int) back to a string so we can see it.

The reason we do this is because a byte is really just a number from 0-255 as it is represented in your computer as 8 1’s and 0’s, called binary. If you don’t already have a basic understanding of how computers store our language, you should get acquainted with it on our encodings page.

Search Buffers

Great, we have a basic program working which can loop over our text and print it out, but that’s pretty far off from compression so let’s keep going. The next step to our program is to implement our “memory” so the program can check to see if its already seen a character.

text = "HELLO"

encoding = "utf-8"

text_bytes = text.encode(encoding)

search_buffer = [] # Array of integers, representing bytes

for char in text_bytes:

print(bytes([char]).decode(encoding)) # Print the character

search_buffer.append(char) # Add the character to our search buffer

We no longer need to output anything as we’re just adding each character to the search buffer with the append method.

Checking Our Search buffer

Now let’s try to implement the LZ part of LZSS, we need to start looking backwards for characters we’ve already seen. This can accomplished quite easily using the list.index method.

for char in text_bytes:

if char in search_buffer:

print(f"Found at {search_buffer.index(char)}")

print(bytes([char]).decode(encoding)) # Print the character

search_buffer.append(char) # Add the character to our search buffer

Output:

H

E

L

Found at 2

L

O

Notice the if char in search_buffer, without this Python will throw an IndexError if the value is not in the list.

Building Tokens

Now let’s build a token and output it when we find the character.

i = 0

for char in text_bytes:

if char in search_buffer:

index = search_buffer.index(char) # The index where the character appears in our search buffer

offset = i - index # Calculate the relative offset

length = 1 # Set the length of the token (how many character it represents)

print(f"<{offset},{length}>") # Build and print our token

else:

print(bytes([char]).decode(encoding)) # Print the character

search_buffer.append(char) # Add the character to our search buffer

i += 1

Output:

H

E

L

<1,1>

O

We’re nearly there! This is actually a rough implementation of LZ77, however there’s one issue. If we have a word that repeats twice, it will copy each character instead of the entire word.

text = "SAM SAM"

Output

S

A

M

<4,1>

<4,1>

<4,1>

Note:

<4,1>is technically correct as each character is represented 4 characters behind the beginning of the token.

That’s not exactly right, we should see <4,3> instead of three <4,1> tokens. So let’s write some code that can check our search buffer for more than one character.

Checking the Search Buffer for More Characters

Let’s modify our code to check the search buffer for more than one character.

def elements_in_array(check_elements, elements):

i = 0

offset = 0

for element in elements:

if len(check_elements) <= offset:

# All of the elements in check_elements are in elements

return i - len(check_elements)

if check_elements[offset] == element:

offset += 1

else:

offset = 0

i += 1

return -1

text = "SAM SAM"

encoding = "utf-8"

text_bytes = text.encode(encoding)

search_buffer = [] # Array of integers, representing bytes

check_characters = [] # Array of integers, representing bytes

i = 0

for char in text_bytes:

check_characters.append(char)

index = elements_in_array(check_characters, search_buffer) # The index where the characters appears in our search buffer

if index == -1 or i == len(text_bytes) - 1:

if len(check_characters) > 1:

index = elements_in_array(check_characters[:-1], search_buffer)

offset = i - index - len(check_characters) + 1 # Calculate the relative offset

length = len(check_characters) # Set the length of the token (how many character it represents)

print(f"<{offset},{length}>") # Build and print our token

else:

print(bytes([char]).decode(encoding)) # Print the character

check_characters = []

search_buffer.append(char) # Add the character to our search buffer

i += 1

Output:

S

A

M

<4,3>

It works! But there’s quite a lot to unpack here so let’s go through it line by line.

The first and largest addition is the elements_in_array function. The code here essentially checks to see if specific elements are within an array in an exact order. If so, it will return the index in the array where the elements start, and if not it will return -1.

Moving on to our main function loop we can see now have check_characters defined at the top. This variable tracks what characters we’re looking for in our search_buffer. As we loop through, we use check_characters.append(char) to add the current character to the characters we’re searching. Then we check to see if check_characters can be found within search_buffer with elements_in_array.

Now we have the best part: the logic. If we couldn’t find a match or it’s the last character we want to output something. If we couldn’t find more than one character in the search_buffer then that means check_characters minus the last character was found, so we’ll output a token representing check_characters minus the last character. Otherwise, we couldn’t find a match for a single character so let’s just output that character.

And that’s essentially LZ77! Try it out for yourself with some different strings to see for yourself. However, you might notice that we’re trying to implement LZSS, not LZ77, so we have one more piece to implement.

Comparing Token Sizes

This crucial piece is the process described earlier of comparing the size of tokens versus the text it represents. Essentially we’re saying, if the token takes up more space than the text it’s representing then don’t output a token, just output the text.

Lucky for us this is a pretty simple change. Our main loop now looks like so:

for char in text_bytes:

check_characters.append(char)

index = elements_in_array(check_characters, search_buffer) # The index where the characters appears in our search buffer

if index == -1 or i == len(text_bytes) - 1:

if len(check_characters) > 1:

index = elements_in_array(check_characters[:-1], search_buffer)

offset = i - index - len(check_characters) + 1 # Calculate the relative offset

length = len(check_characters) # Set the length of the token (how many character it represents)

token = f"<{offset},{length}>" # Build our token

if len(token) > length:

# Length of token is greater than the length it represents, so output the character

print(bytes(check_characters).decode(encoding)) # Print the characters

else:

print(token) # Print our token

else:

print(bytes([char]).decode(encoding)) # Print the character

check_characters = []

search_buffer.append(char) # Add the character to our search buffer

i += 1

Output:

S

A

M

SAM

The key is the len(token) > length which checks if the length of the token is longer than the length of the text it’s representing. If it is, it simply outputs the characters, otherwise it outputs the token.

Sliding Windows

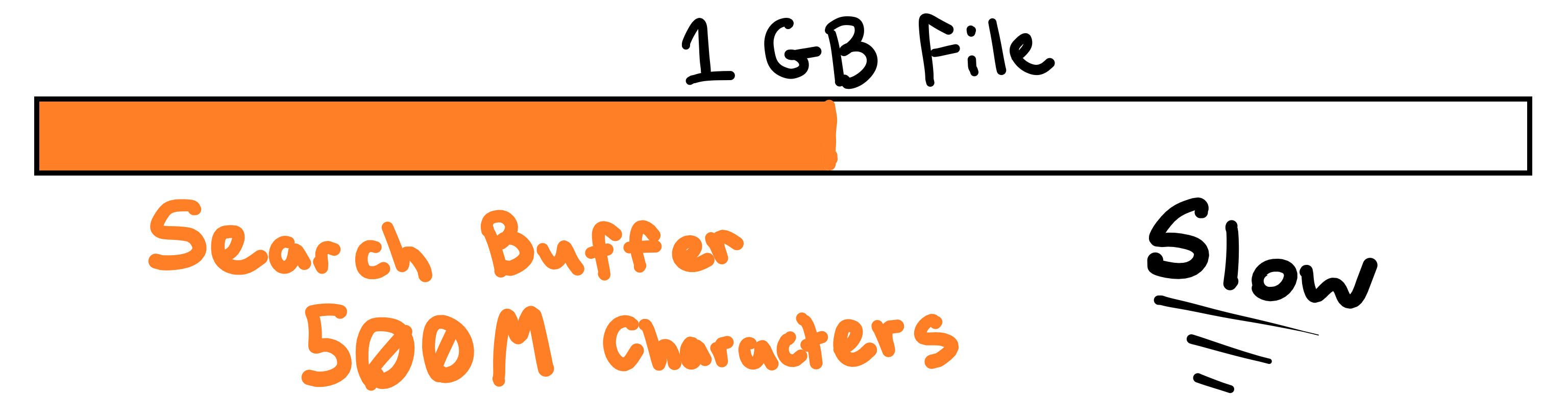

The last piece to the puzzle is something you might have noticed if you’re already trying to compress large file: the search buffer gets big. Let’s say we’re compressing a 1 Gb file. After we go over each character, we add it to the search buffer and continue, though each iteration we also search the entire search buffer for certain characters. This quickly adds up for larger files. In our 1 Gb file scenario, near the end we’ll have to search almost 1 billion bytes to encode a single character.

It should be pretty obvious that this very inefficient. And unfortunately, there is no magic solution. You have to make a tradeoff. With every compression algorithm you have to decide between speed and compression ratio. Do you want a fast algorithm that can’t reduce the file size very much, or a slow algorithm that reduces the file size more? The answer is: it depends. And so, the tradeoff in LZ77’s case is to create a “sliding window”.

The “sliding window” is actually quite simple, all you do is cap off the maximum size of the search buffer. When you add a character to the search buffer that makes it larger than the maximum size of the sliding window then you remove the first character. That way the window is “sliding” as you move through the file, and the algorithm doesn’t slow down!

max_sliding_window_size = 4096

...

for char in text_bytes:

...

search_buffer.append(char) # Add the character to our search buffer

if len(search_buffer) > max_sliding_window_size: # Check to see if it exceeds the max_sliding_window_size

search_buffer = search_buffer[1:] # Remove the first element from the search_buffer

...

These changes should be pretty self-explanatory. We’re just checking to see if the length of the search_buffer is greater than the max_sliding_window_size, and if so we pop the first element off of the search_buffer.

Keep in mind that while a maximum sliding window size of 4096 character is typical, it may be hard to use during testing, try setting it much lower (like 3-4) and test it with some different strings to see how it works.

Putting it all together

That’s everything that makes up LZSS, but for the sake of completing our example, let’s clean it up so we can call a function with some text, an optional max_sliding_window_size, and have it return the encoded text, rather than just printing it out.

encoding = "utf-8"

def encode(text, max_sliding_window_size=4096):

text_bytes = text.encode(encoding)

search_buffer = [] # Array of integers, representing bytes

check_characters = [] # Array of integers, representing bytes

output = [] # Output array

i = 0

for char in text_bytes:

check_characters.append(char)

index = elements_in_array(check_characters, search_buffer) # The index where the characters appears in our search buffer

if index == -1 or i == len(text_bytes) - 1:

if len(check_characters) > 1:

index = elements_in_array(check_characters[:-1], search_buffer)

offset = i - index - len(check_characters) + 1 # Calculate the relative offset

length = len(check_characters) # Set the length of the token (how many character it represents)

token = f"<{offset},{length}>" # Build our token

if len(token) > length:

# Length of token is greater than the length it represents, so output the character

output.extend(check_characters) # Output the characters

else:

output.extend(token.encode(encoding)) # Output our token

else:

output.extend(check_characters) # Output the character

check_characters = []

search_buffer.append(char) # Add the character to our search buffer

if len(search_buffer) > max_sliding_window_size: # Check to see if it exceeds the max_sliding_window_size

search_buffer = search_buffer[1:] # Remove the first element from the search_buffer

i += 1

return bytes(output)

print(encode("SAM SAM", 1).decode(encoding))

print(encode("supercalifragilisticexpialidocious supercalifragilisticexpialidocious", 1024).decode(encoding))

print(encode("LZSS will take over the world!", 256).decode(encoding))

print(encode("It even works with 😀s thanks to UTF-8", 16).decode(encoding))

The function definition is pretty simple, we can just move our text and max_sliding_window_size outside of the function and wrap our code in a function definition. Then we simply call it with some different values to test it, and that’s it!

The finished code can be found in lzss.py in the examples GitHub repo.

Lastly, there’s a few bugs in our program that we encounter with larger files. If we have some text, for example:

ISAM YAM SAM

When the encoder gets to the space right before the “SAM”, it will look for a space in the search buffer which it finds. Then it will search for a space and an “S” (“ S”) which it doesn’t find, so it continues and starts looking for an “A”. The issue here is that it skips looking for an “S” and continues to encode the “AM” not the “SAM”.

In some rare circumstances the code may generate a reference with a length that is larger than its offset which will result in an error.

To fix this, we’ll need to rewrite the logic in our encoder a little bit.

for char in text_bytes:

index = elements_in_array(check_characters, search_buffer) # The index where the characters appears in our search buffer

if elements_in_array(check_characters + [char], search_buffer) == -1 or i == len(text_bytes) - 1:

if i == len(text_bytes) - 1 and elements_in_array(check_characters + [char], search_buffer) != -1:

# Only if it's the last character then add the next character to the text the token is representing

check_characters.append(char)

if len(check_characters) > 1:

index = elements_in_array(check_characters, search_buffer)

offset = i - index - len(check_characters) # Calculate the relative offset

length = len(check_characters) # Set the length of the token (how many character it represents)

token = f"<{offset},{length}>" # Build our token

if len(token) > length:

# Length of token is greater than the length it represents, so output the characters

output.extend(check_characters) # Output the characters

else:

output.extend(token.encode(encoding)) # Output our token

search_buffer.extend(check_characters) # Add the characters to our search buffer

else:

output.extend(check_characters) # Output the character

search_buffer.extend(check_characters) # Add the characters to our search buffer

check_characters = []

check_characters.append(char)

if len(search_buffer) > max_sliding_window_size: # Check to see if it exceeds the max_sliding_window_size

search_buffer = search_buffer[1:] # Remove the first element from the search_buffer

i += 1

To fix the first issue we add the current char to check_characters only at the end and check to see if check_characters + [char] is found. If not we know that check_characters is found so we can continue as normal, and check_characters gets cleared before char is added onto check_characters for the next iteration. We also implement a check on the last iteration to add the current char to check_characters as otherwise our logic wouldn’t be run on the last character and a token wouldn’t be created.

To resolve the other problem we simply have to move the search_buffer.append(char) calls up into our logic and change them to search_buffer.extend(check_characters). This way we only update our search buffer when we’ve already tried to find a token.

Implementing a Decoder

What’s the use of encoding something some text if we can’t decode it? For that we’ll need to build ourselves a decoder.

Luckily for us, building a decoder is actually much simpler than an encoder because all it needs to know how to do is convert a token (“<5,2>”) into the literal text it represents. The decoder doesn’t care about search buffers, sliding windows, or token lengths, it has only one job.

So, let’s get started. We’re going to decode character-by-character just like our encoder so we’ll start with our main loop inside of a function. We’ll also need to encode and decode the strings so we’ll keep the encoding = "utf-8".

encoding = "utf-8"

def decode(text):

text_bytes = text.encode(encoding) # The text encoded as bytes

output = [] # The output characters

for char in text_bytes:

output.append(char) # Add the character to our output

return bytes(output)

print(decode("supercalifragilisticexpialidocious <35,34>").decode(encoding))

Here we’re setting up the structure for the rest of our decoder by setting up our main loop and declaring everything within a neat self-contained function.

Identifying Tokens

The next step is to start doing some actual decoding. The goal of our decoder is to convert a token into text, so we need to first identify a token and extract our offset and length before we can convert it into text.

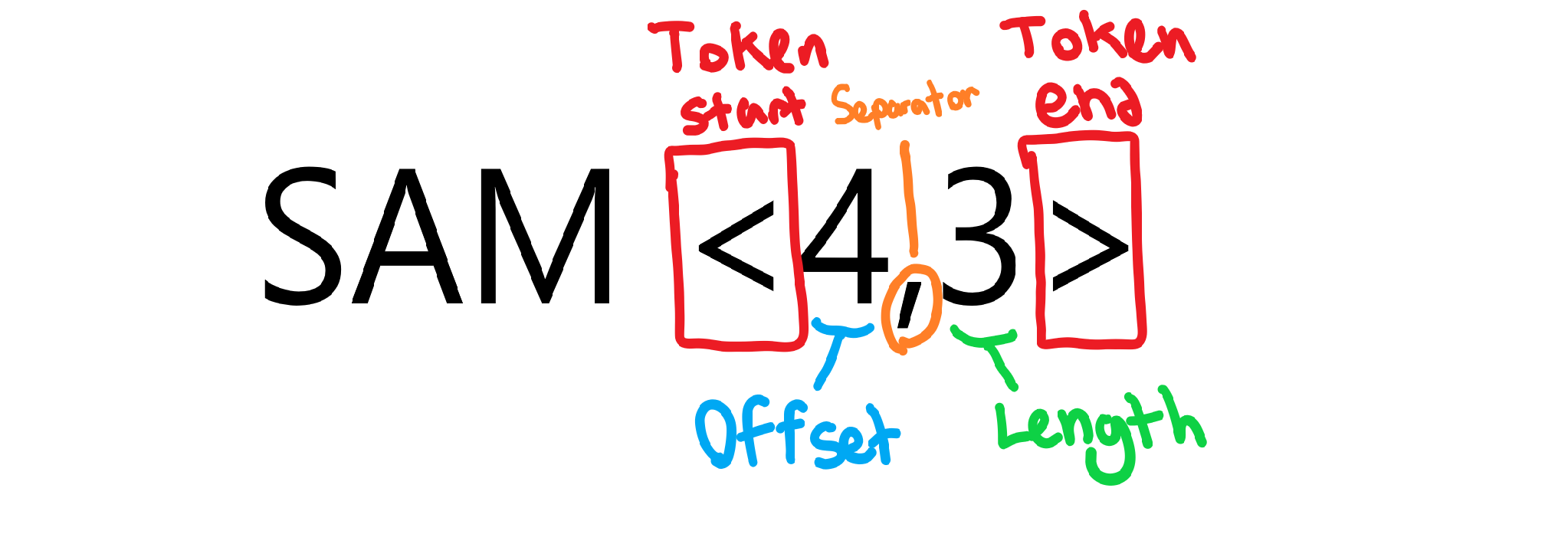

Notice the various components of a token that need to be identified and extracted so we can find the text they represent

Let’s make a small change so we can identify the start and end of a token.

for char in text_bytes:

if char == "<".encode(encoding)[0]:

print("Found opening of a token")

elif char == ">".encode(encoding)[0]:

print("Found closing of a token")

output.append(char) # Add the character to our output

return bytes(output)

Because we’re going character-by-character we can simply check to see if the character is a token opening character or closing character to tell if we’re inside a token. Let’s add some more code to track the numbers between the comma, our seperator.

inside_token = False

scanning_offset = True

length = [] # Length number encoded as bytes

offset = [] # Offset number encoded as bytes

for char in text_bytes:

if char == "<".encode(encoding)[0]:

inside_token = True # We're now inside a token

scanning_offset = True # We're now looking for the length number

elif char == ",".encode(encoding)[0]:

scanning_offset = False

elif char == ">".encode(encoding)[0] and inside_token:

inside_token = False # We're no longer inside a token

# Convert length and offsets to an integer

length_num = int(bytes(length).decode(encoding))

offset_num = int(bytes(offset).decode(encoding))

print(f"Found token with length: {length_num}, offset: {offset_num}")

# Reset length and offset

length, offset = [], []

elif inside_token:

if scanning_offset:

offset.append(char)

else:

length.append(char)

output.append(char) # Add the character to our output

Output:

Found token with length: 34, offset: 35

supercalifragilisticexpialidocious <35,34>

We now have a bunch of if statements that give our loop some more control flow. Let’s go over the changes.

First off we have four new variables outside of the loop:

-

inside_token- Tracks whether or not we’re inside a token -

scanning_offset- Tracks whether we’re currently scanning for the offset number or the length number (1st or 2nd number in the token) -

length- Used to store the bytes (or characters) that represent the token’s length -

offset- Used to store the bytes (or characters) that represent the token’s offset

Inside of the loop, we check if the character is a <, ,, or a > and modify the variables accordingly to track where we are. If the character isn’t any of those and we’re inside a token then we want to add the character to either the offset or length because that means the character is an offset or length.

Lastly, if the character is a >, that means we’re exiting the token, so let’s convert our length and offset into a Python int. We have to do this because they’re currently represented as a list of bytes, so we need to convert those bytes into a Python string and convert that string into an int. Then we finally print that we’ve found a token.

Translating Tokens

Now we have one last step left: translating tokens into the text they represent. Thanks to Python list slicing this is quite simple.

for char in text_bytes:

if char == "<".encode(encoding)[0]:

inside_token = True # We're now inside a token

scanning_offset = True # We're now looking for the length number

token_start = i

elif char == ",".encode(encoding)[0]:

scanning_offset = False

elif char == ">".encode(encoding)[0] and inside_token:

inside_token = False # We're no longer inside a token

# Convert length and offsets to an integer

length_num = int(bytes(length).decode(encoding))

offset_num = int(bytes(offset).decode(encoding))

# Get text that the token represents

referenced_text = output[-offset_num:][:length_num]

output.extend(referenced_text) # referenced_text is a list of bytes so we use extend to add each one to output

# Reset length and offset

length, offset = [], []

elif inside_token:

if scanning_offset:

offset.append(char)

else:

length.append(char)

else:

output.append(char) # Add the character to our output

return bytes(output)

Output:

supercalifragilisticexpialidocious supercalifragilisticexpialidocious

In order to calculate the piece of text that a token is referencing we can simply use our offset and length to find the text from the current output. We use a negative slice to grab all the characters backwards from offset_num and grab up to length_num elements. This results in a referenced_text that represents the token references. Finally we add the referenced_text to our output and we’re finished.

Lastly, we’ll only want to add a character to the output if we’re not in a token so we add an else to the end of our logic which only runs if we’re not in a token.

And that’s it! We now have a LZSS decoder, and by extension, an LZ77 decoder as decoders don’t need to worry about outputting a token only if it’s greater than the referenced text.

Implementation Conclusion

We’ve gone through step-by-step building an encoder and decoder and learned the purpose of each component. Let’s do some basic benchmarks to see how well it works.

if __name__ == "__main__":

encoded = encode(text).decode(encoding)

decoded = decode(encoded).decode(encoding)

print(f"Original: {len(text)}, Encoded: {len(encoded)}, Decoded: {len(decoded)}")

print(f"Lossless: {text == decoded}")

print(f"Compressed size: {(len(encoded)/len(text)) * 100}%")

Using the text as Green Eggs and Ham by Doctor Seuss, we see the output:

Original: 3463 bytes, Encoded: 1912 bytes, Decoded: 3463 bytes

Lossless: True

Compressed size: 55.21224371931851%

LZSS just reduced the file size by 45%, not bad!

One thing to keep in mind is that when we refer to a “character”, we really mean a “byte”. Our loop runs byte-by-byte, not character-by-character. This distinction is minor but significant. In the world of encodings, not every character is a single byte. For example in utf-8, any english letter or symbol is a single byte, but more complicated characters like arabic, mandarin, or emoji characters require multiple bytes despite being a single “character”.

- 4 bytes - 😀

- 1 byte - H

- 3 bytes - 话

- 6 bytes - يَّ

If you’re interested in learning more about how bytes work, check out the Wikipedia articles on Bytes and Unicode or our reference page on bytes.